Doing everything, everywhere, all at once

To MACC or not to MACC

We often hear that to fight climate change we need to decarbonise ‘everything, everywhere, all at once’. UN Secretary-General António Guterres’ even included the phrase in his opening salvo for an IPCC synthesis report.

This is a motivating war cry. But it’s not that helpful for businesses trying to reduce their emissions year on year.

While it’s true that innovative and novel solutions are needed in every sector of our economy, individual businesses need a clear strategy and action plan that they can work towards.

Let’s work through the steps in practice.

Step 1: Baselining and quantifying emissions sources

The first step for any business on their decarbonisation journey is to figure out the quantity of CO2e the business currently produces. I include the ‘e’ for equivalents, as impacts of greenhouses like methane (especially in the agriculture and waste sectors) are sometimes even more pressing than the CO2 component.

The more granular the analysis, the better. Splitting sources into Scope 1-3 is essential, and there’s a myriad of tools for almost all business types to give a good approximation based on expense data.

Estimates on a whole of division or BU level are good, but estimates based on the specific ‘activity’ (e.g. vehicles, flights, waste, energy) are better.

It's also useful for businesses with operations in different jurisdictions to have a site specific emissions estimate to track and measure.

Step 2: Designing emissions reduction activities

This is the hard bit.

Once a business knows its emissions sources, the next step need to figure out the decarbonisation activities that could reduce these emissions to zero.

The simplest way to reduce emissions is reducing (or eliminating) the activity that generates CO2. This could look like driving or flying less, or by running equipment (e.g. HVAC) for fewer hours in a day.

Some activities you can’t simply reduce. Instead, substitutes or new processes are needed. For example, a cafe might change suppliers to receive coffee beans with less packaging, reducing their waste emissions.

The tricky bit of designing emissions reduction activities is costing them. Often a ‘marginal tonne’ approach is useful here. The cost of reducing emissions from large infrastructure upgrades goes down the scale of the capital works increases.

The last resort for hard (read: expensive) to abate emissions is buying offsets1 - this is the ‘net’ part in net zero. This can rightly be part of a businesses transition strategy - however the cost becomes ‘baked’ each year as new credits will have to be purchased.

For any decarbonisation strategy, Step 2 will absorb the lions share of time and effort.

Step 3: Sequencing and financing emissions reduction

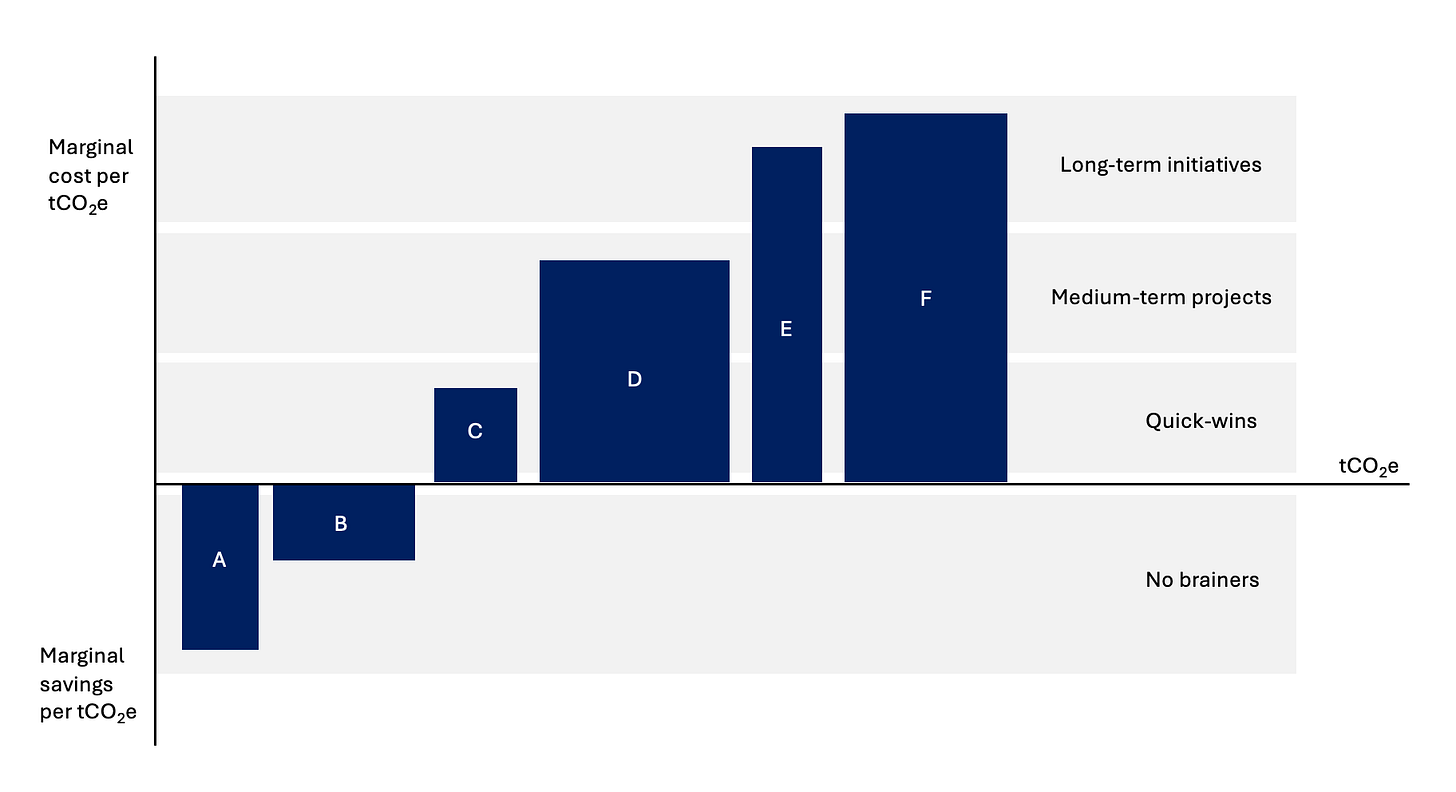

Once you know the approximate cost of an emissions reduction initiative, and the quantity of emissions that could be reduced - it’s time to plot them from least to most expensive.

Since the 1970’s economists tend to call these bar charts Marginal Abatement Cost Curves (MACCs).

Some businesses will have decarbonisation initiatives that save them money right now (the bars below the axis). These are the ‘no-brainers’.

For example, a food processing factory might upgrade to leasing more energy efficient fridges - reducing both their running costs and emissions.

Most businesses should then decarbonise based on their quick-wins - implementing the ideas that are cheap and fast.

It’s also important to invest in R&D for some of the more expensive (or larger) emissions categories. Better technology and operational efficiency brings down overall decarbonisation costs - reducing the need to rely on offsets in the long-term.

Step 4: Getting the most of your MACC

The MACC approach is the best first order response for most businesses, although it’s not without its critics.

Issue #1: MACCs are static

MACCs show decarbonisation costs at a specific point in time. They can’t be ‘set and forget’, as they ignore technological change and learning curves (e.g. input cost reductions or evolving regulatory landscapes). These effects can be both profound and rapid (e.g., solar prices dropping dramatically over time).

Regular input factor updates into MACC calculations (at least annually - ideally quarterly) are best to ensure the state of play is accurately represented.

Some suggest a forecasting exercise to develop a ‘MACC thesis’ on where costs are likely to increase and decrease over time. This is strategy is interesting but high risk - many have been burnt before by delaying action in the hope it’ll be easier tomorrow.

Issue #2: Lack of system dynamics

MACCs treat each emissions measure (i.e. each bar on the chart) as independent. This ignores interactions between initiatives (e.g. how increased electric vehicle adoption affects the grid and renewables).

Individual initiatives on the MACC can be a bit chicken and egg, with capital investment having to happen simultaneous for some projects,

The MACC also fails to account for path dependencies (i.e. how early choices shape future options). For example, if you’ve just invested in a brand new energy efficient office kit out that took years, you might be reluctant to move to new premises as the business grows.

Issue #3: Practical and equity blindness

Global businesses with several site locations or complex internal supply chains often run into curious predicaments if they produce a company-wide MACC. It’s often cheaper to reduce emissions in less developed countries2 than it is in the OECD.

Following the MACC approach, this makes perfect sense. Yet on a practical basis, it is unviable for a large multinational (think Coca Cola or Nestle) to invest in emissions reduction in SE Asia and South America while doing nothing in the U.S.

Regulators wouldn’t allow it - and customers would be outraged. The simplest solution here is to have country specific MACC tailored to addressing the local emissions targets.

The upshot of it all

Despite their limitations, MACCs are still one of the best tools we’ve got for decarbonisation prioritisation.

Grand slogans may stir hearts, but it is marginal abatement cost curves - plotted, updated, interrogated - that steer real progress.

For firms, the future will belong not to those who promise ‘everything, everywhere, all at once’, but to those who deliver the right thing, in the right place, at the right time.

That’s a less catchy but far more impactful rally cry.

I’m make that trade-off any day of the week.

Rather than ‘offset’, the term should be ‘project finance carbon removals’ although I’ll admit there is a bit less of a ring to it

The same logic applies for buying offsets in LDC’s